Spaced Learning – How To Use The Spacing Effect In Your Company

Extraordinary progress in neuroscience is teaching us more about our brains than ever before. But despite our growing preoccupation with productivity and efficiency, most of us haven’t changed our learning habits. So, we decided to ask a neuroscientist how to become better learners.

In our first Podcast Episode we spoke to Marie Lacroix, Co-Founder of Cog’X, a cognitive science consultancy and study agency. Through their consulting and training services, Cog’X helps companies improve their innovation processes and raise awareness on what cognitive sciences tell us about performance and well-being.

Learning Means Changing Our Brain Physically

Our brain houses about 86 billion neurons. They are the primary functional unit of the nervous system, connect in a vast network, and further organize in larger functional regions of our brain.

So, our brain is fundamentally a network of neurons. Those neutrons are connected by synapses, and it is those synapses that change when we learn. When we experience learning, a synapse gets reinforced, the activity changes the weight of the synapses and the actual makeup of our brain changes.

“One definition of learning from a neuroscientific perspective would be to change our mental representation of behavior through experience”, says Marie, “and this happens throughout our lives.”

We Don’t Retrieve Information Like a Computer

Since time immemorial, humans have tried to describe our brain by comparing it to the latest technology. It has been compared to a clock, a switchboard, a computer and most recently, a network. The latter seems to accurately describe the fundamental working of our brain.

When we learn, we create memories, but these memories are not like one individual piece of data. Memories are not located in any one part of the brain. Memories are formed in a process that involves the entire brain.

If you think about your favorite food or recipe, different parts of your brain will have encoded the smell, the ingredients, and the emotions it made you feel. Several different elements create a logical whole. When you think about your favorite food, a network of neural patterns piece the image together. We don’t just store memories as a whole. We can’t just ‘tell’ ourselves to remember something.

When we experience something, neurons are activated. This leaves a print in our brain, called the encoding of information. “This is one very small part of the learning part because we actually forget most of the information the brain receives”, says Marie.

What happens next is called consolidation, the process that makes learning stick for the first time. And lastly, the third part of learning is retrieval; this is where we access the print that we made in our brain.

Retrieval is a fundamental part of learning and is often the part we forget to train. Marie uses this example: “I spend all my day reading articles in English, encoding the English words, and retrieving the words and information in English. Then, when I speak in English, it needs effort to get to those words, even though I encoded and consolidated it.”

Let. It. Sink. In.

“Learning occurs best when new information is incorporated gradually into the memory store rather than when it is jammed in all at once.”

– John Medina, Brain Rules

Intuitively, we know that frequency and repetition are important to learn, but neuroscientists are getting better at exploring how efficient this process could become.

There are strategies that we are quite familiar with, such as learning everything last minute before a test and recall it from our short term memory. We hope the adrenaline might focus our mind that little extra bit to get us over the line.

Unsurprisingly, it’s not a tactic that will make us smarter in the long run. Studies have shown that while people do believe themselves to have mastered what they have learned, they consistently overestimate how much they retain.

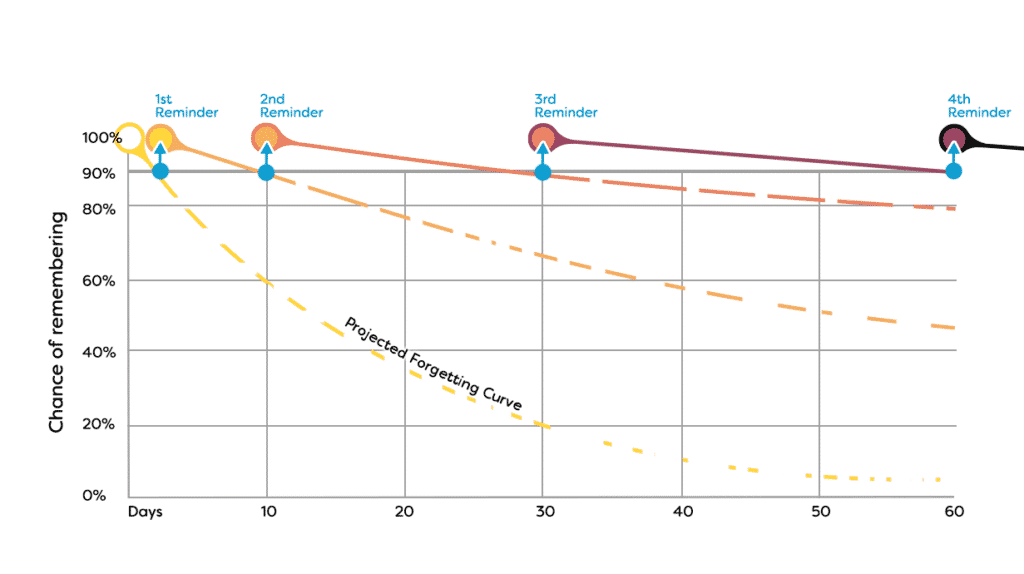

A more useful concept is “Spaced Learning” or “Spaced Repetition”, which revolves around slowing down the process of forgetting. Instead of repeating something many times — “hammering it in” so to speak — spaced learning focuses on increasing gaps between repetitions.

This does not come intuitively to most people, which also explains that people who use this technique feel less confident. However, they usually outperform others when tested.

The key is to repeat the learning at the right time!

How to Use the Spacing Effect

This is not being taught in schools yet, so take note for yourself, and maybe pass it on too.

Spaced learning is difficult because it requires quite a bit of planning.

There are researchers and software developers who are using computer algorithms to try to help students optimize their studying. These algorithms help you learn by sorting information based on your responses to questions; so they will automatically prioritize questions you answered incorrectly and at the right time.

For those of us who are not studying medicine, a simpler system might already help us save some time and improve our ability to learn:

A typical spaced repetition system includes these key components:

- Basic Reviewing Pattern: The basic concept is to review for example after one hour, then a day, two days, a week, a fortnight, then monthly, then every six months, then yearly. Correct answers move to the next level and will be reviewed less often and vice versa.

- Organization: Cards or a software can help to keep track. Some people swear the act of creating cards is helping too.

- Rewards: Learning programs like Duolingo do this well. There are points to score, daily goals, and so on.

- Time Box: Learning requires focus, and it takes time to get into the perfect state of mind. However, we start losing the ability to process new information quite quickly. It’s usually advised to not spend more than 30 minutes on a review session.

Exactly why spaced learning works is not fully understood yet. We know that repetition signals a higher priority in our brains. Things we see and hear often will be given a higher priority. We recall our address, phone number, passwords, etc. without struggle.

Spaced learning seems to rely on other factors too. Just when we are about to forget something, reinforcement will be most effective. Practicing and testing knowledge is as effective as teaching somebody else. They are processes through which we find out what we have forgotten. And in a similar way, the harder it is to remember something now, the easier it is to recall it in the future.

How is this Relevant for Organizations?

When we talk about learning organizations, we mean a place where learning doesn’t feel like memorizing things, but where — through learning and experience — our judgment is improved, our connections to others strengthened and therefore our ability to find solutions and innovate together increases.

That seems to be a million miles away from a medical student learning the name of every bone in the body. Most of us don’t learn like students anymore. It is not about memorizing huge amounts of data.

And yet, our brain learns, changes our mindset and our behavior the same way. It is encoding, consolidating and retrieving inputs and experiences. It doesn’t need any less attention and focus.

How often do we have the time and space to learn a new skill and acquire new knowledge so deeply, that we become masters at it? Doesn’t it usually feel like we are one step behind? We design slide decks, copy-paste, click through an online learning module — and we hope that our brain keeps up.

While that works to a certain extent, this modus operandi is also a barrier to change. It doesn’t allow the space to let things sink in.

For the leadership challenges of today, the brain needs to perform at the highest level. Learning about new technologies, understanding clients and markets better, becoming more confident in product knowledge, being empathetic and inclusive — all these things require us to make new connections and change the fabric of our brain. Are we giving our people the right skills, tools, and spaces to learn?

Author

Subscribe to get Access to Exclusive Content